You Have to Do the Hard Stuff to Do the Fun Stuff

Tyler: And so that kind of gave me a taste for it, because I had all of these guys coming in and pitching. They were startups at the time, or small tech companies that were in ad tech. I thought, "Here I am on the buy side, trying to optimize." Really cool, but I really liked what they were doing, and sort of saw the light, if you will. Decided it was time to get involved.

Suzanne: You envied the entrepreneurial spirit.

Tyler: Certainly.

Suzanne: Right. You came out to LA, you put a surfboard in the car. There was no looking back.

Tyler: Yep.

Suzanne: Now we're here at BCG Ventures. Give us the ... What is BCG Ventures?

Tyler: Yeah. I have a job now, so obviously the startup didn't work. I work at Boston Consulting Group Digital Ventures, here in Manhattan Beach. We are a corporate innovation and incubation firm. Essentially, what we do is we partner with large corporations, and we look for opportunities to leverage their assets, and any frictions that they have, either with their customers or within their own company, to develop growth opportunities through the form of a new venture. What we do here is we actually try to come up with what those ventures are going to be in partnership with them. We have sort of an innovation cycle, if you will, where we spend a number of weeks working with a client, coming up with these ideas, and really ideating around concepts that might help them to either reach a new market, or reach a new customer.

Suzanne: Now, you joke about having a job, but actually, what's going on here, is you're all just running around like entrepreneurs, sort of creating these micro-businesses or startups' ideas, and pitching them to clients, big clients, who are saying, "We're stagnating," or, "We're getting cannibalized by startups. How can we think lean?" It's almost intrapreneurial, in this way.

Tyler: Yep. It is.

Suzanne: Outsourced intrapreneurship, if you will.

Tyler: Yeah, it is. It's definitely an interesting place, and it's very unique, because we have access to so many things that a typical startup wouldn't have access to, or a typical entrepreneur wouldn't have access to, whether it's tools, or capital, or the clients, and huge data sets that they haven't leveraged. We're really looking for those interesting ... We're not starting from zero. We're starting with all of these things, and you have to come up with creative ways to mash them up to make something beautiful. We've come up with a few. I'm working on a few now, and we're hoping for something big. We've only been around for two years, and it's crazy, we're growing insanely fast. We're now in Tokyo, in Sydney, London, Berlin, and the types of projects we're working on are definitely interesting.

Suzanne: Cool.

Tyler: Yeah, it's great.

Suzanne: Your title is, "Product Lead?"

Tyler: Product manager, yes.

Suzanne: Product manager. Okay. What does that mean from ... I'm looking at you, and I wanted to say, "9 to 5," but I almost want to edit it and say like, "10 to 4." Is that insulting?

Tyler: No, that's not insulting.

Suzanne: You look so relaxed.

Tyler: I told you, I went surfing this morning. No, 9:30, but actually I'm here till 9 or 10 at night most nights. I think it's just because I really like what I do, and I find it interesting, and just see great opportunities with the stuff that we're working on. When you're passionate about your job, it doesn't feel like you're working.

Suzanne: Describe a typical day. I'm sure there isn't such thing as a typical day, but what are some of the things that you get your hands into between 9:30 and whenever you go home.

Tyler: As a product manager here, it's really interesting, because each one of our ventures is in one of three stages. It's either in what we call, "Innovation, Incubation, or Commercialization." In innovation, project managers here get discounted a little bit. If you're on an innovation, everybody's like, "Oh, are you going to be okay? It doesn't have a real defined process, nothing's really ... Are you going to get upset? Are you going to know what to do?" You'll see product managers that are like, "Oh, I hate innovation. What is this, this whole customer journey, and understanding the consumer, and then ideating, and all of that?" I find it really interesting. It's where a lot of the vision comes, and the spark of potential ideas, but there is a lot of work that goes into it that doesn't turn into a tangible product, and I think that's what ... The typical product manager is like, "Well, what? It's not ... I can't touch it. I can't improve it. What is this concept thing?"

When we get into incubation, that's where, actually, our company has decided upon a product out of innovation, based on all of the criteria that we put in place to essentially determine that it gets the thumbs up, and is going to move forward. In incubation is where the building begins. Incubation is where our product managers are happy and loving life, for the most part, because it's essentially been turned over to them to now lead the teams, and to say, "Okay, we need to build this thing. We need to get it in market." You get assigned a team of designers and a team of engineers, and you get to build. That's the real beauty, and you're bringing something new to market.

Then, in commercialization is where we actually commercialize the product, put it into market. A lot of times, given our relationship with our corporate clients, here at DV, at that point, sometimes our product will get handed over to them to begin running, and we get to hop back in line and do it again. Other times, some of ours are more joint ventures, where DV has a stake in it as well as the corporate client, and in that case, we'll bring it to market, we'll continue to iterate, look at the analysis of data, and how consumers are interacting with it, and continue to build and improve upon the product.

Suzanne: That's when an internal product manager almost gets shipped off to a new base. They're like, "You did such a great job commercializing this product, that you're now working for them, essentially."

Tyler: That is actually kind of the dream here.

Suzanne: It is the dream? Oh, okay.

Tyler: For some. For some, it definitely is. For me, it is. The reason why, for me, is because I feel like there's something about this place that's almost ... I call it a startup without the risk, in the sense that we're working really hard to create really cool stuff. I'm still going home with a paycheck. I have the benefits of working at a really big company, and then if one of these products goes to market, we do have opportunities where ... There's a number of them currently, where the C-Suite are guys that left from here to now run the product, or the company. It's backed by either BCG, or by our corporate client. We're not getting founder's equity, by any means, but you're now running a venture and a lot of times, you have an incredible client already, as your first customer, because it's someone that we already worked with. It really enables you to have an insane amount of momentum right out of the gate. We have a few that have just hit that stride, and some guys have left, and it's really exciting. I think it's a really cool opportunity.

Suzanne: You're poking into rooms saying, "Anybody looking for a PM to steer this ship?"

Tyler: Yeah, I mean a guy just left a couple of weeks ago to go lead a product that we just launched in China. Another one recently, in the last six months, out of San Francisco. There's quite a few that have happened like that. It's neat. Of course, DV doesn't want to lose good people, but also, when it's the lead investor in one of these products, and they know that the person running it is from here, and knows the DV way, it makes for a little bit of comfort in knowing who the founder is.

Suzanne: Right. It's interesting that you say that there's a sentiment that innovation is ... It sounds a little bit like the innovation phase, as you define it here, is like being an entrepreneur with an idea, and if you're a smart entrepreneur, and you've read a little bit about how to mitigate risk, then what you're doing is you're thinking about a concept, you're validating it, you're doing some preliminary customer development. This is the truth that the romance wipes away when you introduce validated learning as a concept, because as long as you're sitting around thinking that the only thing standing between you and a two billion dollar acquisition is somebody like me to build the product for you, then everything is kind of rosy and perfect.

Tyler: Right.

Suzanne: It's when you actually take your idea, and then start talking to people, and realizing you don't fully understand the problem, or the solution that you've perfectly imagined when you jumped straight to features in your mind, is actually not really going to solve that problem. You have to pivot, you don't know what. You lose interest.

Tyler: Totally. No, it's very true, and I think that that's kind of that ... Like you said, it's like the reality of ... taking the reality of the dream, and really defining what it can become. Yeah, some product managers get caught up in that space of, "Oh, I don't know. Is this right? I'm not comfortable. Just give me something, and let me run with it, and let me start to build." It's interesting here, but I enjoy both, so it's been a good fit.

Suzanne: It speaks to, I think, the difference of a product management role, moving from one place to another. If you're in an organization that is a true startup ... I'm not talking about a fully capitalized, everyone's got a new Mac startup, but I mean the garage startup, if you will. There's a sense of, "I'm touching development, maybe," or, "I'm touching design, I'm making calls. No one's picking up the phone, but I'm making them."

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: What it means to be a product manager in that capacity starts to become loose. It's more, "I'm doing everything."

Tyler: Right.

Suzanne: Versus that really delineated space that says, "Great. Here's your dashboard, here's your respective teams." You said you like both. What do you think is more interesting?

Tyler: It's funny the way you just framed that out, because I started thinking through each person that I know here, that's a product manager, and where they came from, and then what they like. The product managers that I know that have come from Amazon, and Beats, Google, more structured PM roles, they're the guys that don't like innovation. They're the guys that have had a command post, have had their people building things, and feel really comfortable in that setting. Then, it's the guys that have done the startups, and done other things, that haven't been as straight PM roles, that are like, "Innovation's great. I have fun, I can do the vision piece." I think that the innovation is interesting, and, obviously, important, because you can't get to incubation without good innovation, at least in the way that we define it here at DV, but I still think that the ... Incubation is where you start to build.

I think that you look at companies like Nike, where prototyping is their number one North star. "Just get in there, start making it, put it on someone's foot, and if it works, it works, and then we'll spend more time on it." Here, it's not until innovation ... I apologize, incubation. End of innovation, we start doing a little bit more prototyping and stuff, but I think because of that relationship with a corporate partner, and trying to help guide them through the process, and make them comfortable with it, it's really hard for us just to stick a crappy looking prototype in front of them, and to justify working with us, and fees, and that sort of thing. They're like, "Well, what is this? This isn't what we paid for?" It's like, "Well, it's an MVP, this is how you get to things."

It doesn't really work that well in our model, so we have to do a little bit more of the coaching and understanding of how we're doing these things, and why we're doing them. Then, when we get to incubation, they've kind of bought in. It's at that point where we're like, "Okay, great. I'm glad you guys have this grand vision. Let me show you what it's going to look like on day one, and we're going to get there, but it's not going to be there tomorrow. There's a way and a path to do it, and we're going to learn a shit ton along the way. Maybe it looks like that, but maybe it looks like a completely different version of that, but it's going to be guided based on more user interaction, and testing. We're going to make sure that what we develop is the right thing." To me, that build is where the rubber meets the road, and that's what's exciting to me, because it really starts to come to life.

Suzanne: You talk about these corporate clients. We're talking about Fortune 100 companies, here.

Tyler: Yep.

Suzanne: Do they have product managers?

Tyler: In some instances, yes. In others, no, or we don't interact with them, necessarily. We're talking about ... A large portion of our portfolio is major insurance providers, and we have a number of major pharmaceutical players. Yeah, they're going to have product managers to some degree, but where we're tapping into things with them normally doesn't involve their product managers, no.

Suzanne: When you tell your friends and family that you're a product manager, do they know what you're talking about?

Tyler: No.

Suzanne: No? What do your friends and family think that you do all day?

Tyler: Actually, it's funny, because some people do, or they think they do, and they're like, "Oh, wow. That's super technical. You're developing stuff? How do you manage all of that, and what do you do?" It's a good question. Because I started in consulting, and they all watched me do that, and I'd had a lot of conversation with that, and then I left, and I build a couple of mobile apps, myself and one engineer, it at least gives some context. People that know me, I'm able to be like, "Well, it's kind of like you took the two, and you cram them together. I'm talking to these clients, but then instead of just giving them strategy and power point decks as to how to improve their business, I actually go out and build them an app, or a platform, or something that's actually going to help them solve that problem." Through that interaction and dynamic, it at least helps them to understand a little bit more. A lot of times I just avoid it. I'm like, "Yeah, it's really fun. I love my job. It's great."

Suzanne: I bring it up, but there's some truth to this. Part of the reason that '100 Product Managers Show' exists is because we're trying to demystify this domain called "Product Management," even for those of us who are actively involved in it. I hope part of the appeal for people listening in is saying, "Oh, that's what everyone else is doing?" Then they're kind of measuring it against what they're doing. We're starting to feel not so alone in our little worlds of ... Everyone's kind of winging it, it's Wild West a bit, right now.

Tyler: For sure. No, I'm with you. It was like that when I interviewed here. I came in for an interview. DV's only been around for two years, but I interviewed with a couple different product managers, and they were all very different. Some of them had come from being engineers, and having a much more development side, and others had come from consulting. With DV in particular, I think that we have that ability to have a broader base of what a product manager's capabilities are, because of the cycles that we go through. Some can focus just in innovation, if they want, and others can be more of our builders. Everybody, at least, has that sense of viability, feasibility, like, "Can we actually build this thing? Can we bring it to market?" There's going to be some guys that are going to be a lot better at actually writing user stories, and ensuring that it meets every specification, and that the developers are going to understand it, and that the designers are going to be able to create to that time schedule, and sprint cycles, and all of that.

Then, there is more of that visionary product piece here. I think that you have to ask a lot of questions when you go into a role, because the definition of "product" is so different at different places, to make sure that you're going to be comfortable with what you're doing. I think that if you go in someplace, and they're expecting you to be the technical product manager that's writing user stories every day, and guiding a team of engineers, and you haven't done that previously, or don't have a lot of engineering experience, you're going to find yourself in a really uncomfortable position really, really quickly.

If it's more of the startup that you mentioned, where you're going to have to wear a lot of hats, and you're going to have some time to develop some more of those skills, you can get pretty comfortable in that space. I think I got lucky here, with having a little bit of both. Having built two apps on my own, I at least had sat down, and I had gone from wireframing on a piece of paper, to using Sketch, to actually doing some of the design work. Then, to sitting with an engineer, 14 hours a day, going through, and understanding how he was building what he was building, teaching stuff on my own. I had some of those skills, but that's definitely a piece that I continue to try to develop on the technical side, because I think that that's where you can really differentiate yourself.

Suzanne: When we talk about product management, it's the Neapolitan swirl of business, technology, and design. Oftentimes, in the least, you sort of need to come in from one domain. It sounds like part of your background really came from understanding that business, business objectives, business model design, and then, as you say, from your own entrepreneurial ventures, learning a little bit more of the hands on. Do you think there's a sweet spot? If you were going to talk to some young Jedi and say, "So you want to be a product manager? My advice, as Tyler here, speaking, is go and be great at this, and a bit of this." What would be the combo that you would recommend? Skill sets?

Tyler: Yeah. The good part about product management is that I think that the majority of the skills you can learn. We're not talking about something out there that's impossible to obtain. The technical stuff, you can sit down, you can take a course, you can teach yourself how to code. There's plenty of tools and resources out there. Design, same thing. I think design, just having a sense of appreciation for good design, a sense of good design, teaching yourself a little bit online. Again, that's not a huge one. I think business becomes a little bit more challenging in the sense of ... just depending on what it is you're doing, and here, we have to really adapt, because one month you might be working with an insurance client, the next month you might be working with a healthcare client. The next month you might be working with a consumer goods client, so being able to bounce from one to the next. Here, the design and technical pieces kind of stay the same, the business sides change a lot. That piece, to me, has been very valuable, with my background, but honestly, I think the number one skill is adaptability to different personalities.

You have to be a true leader, and when you sit down and have a conversation with a designer, it is going to be a complete 360, or 180, when you go and sit down and have a conversation with an engineer. When you all of a sudden have a team of 12 people that are looking to you to guide them in what it is that you're creating, if you can't adapt to each one of those personalities, and get everyone working together collectively to drive to the goal, you're going to really struggle. You're definitely going to struggle, and I've seen it. I'm fortunate in the sense that I've always been pretty outgoing and adaptable, and can converse with just about anybody, and enjoy it, but the butting of the heads of when product wants to do one thing, and engineers think it should go another way, or design thinks it should happen another way, can be tough. It can be really straining on a manager in that role, so being open and understanding of those perspectives, and why they have those perspectives, is really powerful when you're leading a team.

Suzanne: What does it take, in your opinion, to get a job as a product manager? The classic conundrum of, "How do I get experience if I don't have experience?" Say I'm a student at General Assembly. I'm taking a product management course. I want to come and work here. How do I get in?

Tyler: That's a great question. With product, I think that ... With anything, do whatever you can to prove that it's really what you want to do. There's so many easy tools and things out there now that would enable you to sit down and create. Go home, wireframe something, put it in vision or in design, and make, essentially, a prototype. Make it your damn resume, make it the last five years of your life, whatever you want to make it, tell a story with it, that represents you, and why you think that product management is right for you. Although there's sometimes the gimmicky resumes that get shared on LinkedIn of this designer, or this and that, but it kind of proves your passion towards it. I think that any organization that sees that you have a drive for a particular area, and why you want to do it, at least any good organization, might be open to it if they have a low enough role available.

Whenever I work with people, I just want to see that they're hungry to learn, and hungry to expand their skill sets. I think that there's so many ways to prove that now, whether it's like you said, going and taking a class at General Assembly or taking a course online, or building a mock product just to build it, and prove that you really want to do it, and not just say, "Hey. I really want to be a product manager." I think because product has those different facets of business, of design, of technical capabilities, pick one, and do it really well, and then kind of brush up on the other areas to round yourself out. It gives you some leniency and flexibility. It's not so rigid that you should be able to find an area that you can really shine in, and prove why you'd be good at that role. I hope that makes sense.

Suzanne: Yeah. Go out and get it done.

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: This has come up before, this concept of side projects. It's interesting, because-

Tyler: Always got to have a side project.

Suzanne: You always have to have a ... Even still, no matter what, this topic of internships comes up a lot, and there's a lot of debate about wages, and certainly, in the world of development, increasingly in design, commoditization, and at the same time, there's a reality that you have to put in the time, and the sweat, and the tears, and show that you really want to be in it. Proving yourself as a product manager is a little bit like going to live in New York. You have to ... "Can you make it?"

Tyler: "Can you handle it?" Yeah.

Suzanne: "Show me."

Tyler: Yeah. I'm totally with you, and it's true. Internships are great. I get asked about internships, sometimes, from family members that are in high school. I had some crappy internships and I had some decent internships, but I made sure I never did the same thing twice, just because I didn't know what I wanted to do. It helped me by recognizing really what I didn't want to do. I went and worked for a stockbroker. I went and shot TV commercials. I worked at a summer camp. I did all sorts of different stuff, but I think, again, what I recognize was that almost enabled me more in my role today, because I was working with a lot of different personalities. I was working with a lot of different people. That people management is, like I said, one of the most valuable skills that I think I bring to my job today. If I had just worked with the exact same type of people, no matter what the role was, maybe the technical skills within that specific subset would have enhanced, but I don't think I would have been as rounded out in my ability to do what I can do now from the management side of things.

Suzanne: What's the least sexy thing about product management? Just put it out on the table. We're demystifying here, we're unpacking. The thing that's like, "Oh, God." That's not so cool.

Tyler: Yeah. Not so cool? Yeah. When you're creating, and you're sitting there, and you're writing user stories for a sign-on page, and you have to think through every single detail, and hover state and all of these things. You're just like, "All right. Come on. Can we get to the fun stuff?" There's definitely pieces of that, but-

Suzanne: The fun stuff being the design, and the-

Tyler: Yeah, design, talking through it.

Suzanne: "Bring me colors and type face. Let me touch it."

Tyler: Yeah. Exactly. Sitting there, and making sure you don't forget everything, and people looking to you to make sure you have it, and making sure that you have every one of those details, it's tasking, but you've got to do the harder stuff to get to do the fun stuff.

Suzanne: Right. Fair enough. Normally I asked people at the end of our conversation, "What's your personal quote or mantra that goes on a mug?" Is it that one? You have to do the hard stuff to do the fun stuff? Do you have a better one? One that you use on the beach, maybe?

Tyler: One that I use on the beach? "Get shit done," is pretty much what I have to say. That's how I operate, and it's worked out pretty well so far, so I'll continue to do that.

Suzanne: What about resources? Do you listen to podcasts, or follow any sort of bloggers, or thought leaders? Is there anybody in this space that you think is, "If you are not familiar with their work, or the theories that they're bringing into the industry, you need to get familiar with them?"

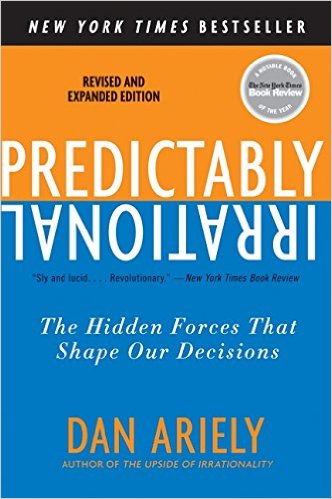

Tyler: I do listen to quite a few podcasts. I got into swimming. Swimming, I thought, was so boring, but then I bought a waterproof iPod, so I just plug in a podcast, I'll swim for like 30 minutes in my pool, and then get out. It's amazing, so I can kill two birds with one stone. I listened to Startup for a while, I listen to Tim Ferriss. Again, I'm in the camp of diversity of thought. I don't want to listen to the same people talk about the same stuff, necessarily, because I think that I can learn more from hearing about some crazy scientist that's working on something crazy, or going to Mars, because maybe it ties back, or gives me inspiration, or creativity, towards a new challenge. I do that quite a bit. I like to read a lot. 'Predictably Irrational' is the last book I read, and I just finished that. It was a great book, and really cool as a product manager, too, because you'll catch yourself a number of times in reading the book, of like, "God damn it, I do that, too." All of these things where-

Suzanne: I'm not familiar with it. What's-

Tyler: Oh, it's a great book.

Suzanne: Coles Notes, please.

Tyler: I can't think of the author right now, but it's called 'Predictably Irrational.' It's all about how humans are predictably irrational. A lot of the things that we do, we're going to do, and they're completely irrational, but based on data, and statistics, and the longevity of us doing the exact same thing, we know we're going to do it. It is really, really interesting. You'll see some things in there, and a lot of it's geared towards how to develop products when people are irrational. You might think, "There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this." Then, sure enough, "Boom." Everybody chooses it.

Suzanne: You mean as customers, or even internally?

Tyler: Both. Yeah, it kind of has both perspectives throughout the book, but it's great. You should definitely read it.

Suzanne: The danger, too, is always ... We know so much about all of these different disciplines that we cook up all of these assumptions all the time about how other people outside of the world of product think about user experience, think about design, think about features. It's funny, the number one problem is jumping to the solution, because that's the fun stuff, when you say it.

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: How do you insert into your memory muscle, "Don't leap from an unexamined assumption to build. Remember to go through those boring steps that you probably all do here in innovation." How do you insert it so that you don't forget to make the same mistakes that you're trying to teach your clients not to make?

Tyler: It's a hard one. It is a hard one, because you have a grand vision of what something's going to look like, or how you want it to be at scale, or how it's going to appease all of these customers, but then you have to recognize that it is a long hallway to get there. You've got to start somewhere, and you've got to start somewhere that's easy, and that's going to captivate an audience before you actually get to that platform play, if you will. That's really the role of product here, because we have so many design thinkers, we have business folks, we have people that are like, "Oh, well can't we just do this?" This is great. We pitched three concepts last week, and after all three were over, there was a couple people in the room that were like, "Let's just combine those. That's perfect. That product would be amazing."

We're like, "Yeah, that product would be amazing if you want it in ten years. You don't understand what you just asked for, and it just proves that you're not understanding what the customer's pain point it. We need to figure out what that actually pain point is, and try to solve it, because if we can solve that really well, well then we can add these other pieces as features." I think that having that clarity as a PM is really important. You do have to remind yourself of that, because you can get hung up. I've done it. I did it on my own startup. ht now, but it's called 'Predictably Irrational.' It's all about how humans are predictably irrational. A lot of the things that we do, we're going to do, and they're completely irrational, but based on data, and statistics, and the longevity of us doing the exact same thing, we know we're going to do it. It is really, really interesting. You'll see some things in there, and a lot of it's geared towards how to develop products when people are irrational. You might think, "There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this." Then, sure enough, "Boom." Everybody chooses it.

Suzanne: You mean as customers, or even internally?

Tyler: Both. Yeah, it kind of has both perspectives throughout the book, but it's great. You should definitely read it.

Suzanne: The danger, too, is always ... We know so much about all of these different disciplines that we cook up all of these assumptions all the time about how other people outside of the world of product think about user experience, think about design, think about features. It's funny, the number one problem is jumping to the solution, because that's the fun stuff, when you say it.

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: How do you insert into your memory muscle, "Don't leap from an unexamined assumption to build. Remember to go through those boring steps that you probably all do here in innovation." How do you insert it so that you don't forget to make the same mistakes that you're trying to teach your clients not to make?

Tyler: It's a hard one. It is a hard one, because you have a grand vision of what something's going to look like, or how you want it to be at scale, or how it's going to appease all of these customers, but then you have to recognize that it is a long hallway to get there. You've got to start somewhere, and you've got to start somewhere that's easy, and that's going to captivate an audience before you actually get to that platform play, if you will. That's really the role of product here, because we have so many design thinkers, we have business folks, we have people that are like, "Oh, well can't we just do this?" This is great. We pitched three concepts last week, and after all three were over, there was a couple people in the room that were like, "Let's just combine those. That's perfect. That product would be amazing."

We're like, "Yeah, that product would be amazing if you want it in ten years. You don't understand what you just asked for, and it just proves that you're not understanding what the customer's pain point it. We need to figure out what that actually pain point is, and try to solve it, because if we can solve that really well, well then we can add these other pieces as features." I think that having that clarity as a PM is really important. You do have to remind you

Tyler: I can't think of the author right now, but it's called 'Predictably Irrational.' It's all about how humans are predictably irrational. A lot of the things that we do, we're going to do, and they're completely irrational, but based on data, and statistics, and the longevity of us doing the exact same thing, we know we're going to do it. It is really, really interesting. You'll see some things in there, and a lot of it's geared towards how to develop products when people are irrational. You might think, "There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this." Then, sure enough, "Boom." Everybody chooses it.

Suzanne: You mean as customers, or even internally?

Tyler: Both. Yeah, it kind of has both perspectives throughout the book, but it's great. You should definitely read it.

Suzanne: The danger, too, is always ... We know so much about all of these different disciplines that we cook up all of these assumptions all the time about how other people outside of the world of product think about user experience, think about design, think about features. It's funny, the number one problem is jumping to the solution, because that's the fun stuff, when you say it.

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: How do you insert into your memory muscle, "Don't leap from an unexamined assumption to build. Remember to go through those boring steps that you probably all do here in innovation." How do you insert it so that you don't forget to make the same mistakes that you're trying to teach your clients not to make?

Tyler: It's a hard one. It is a hard one, because you have a grand vision of what something's going to look like, or how you want it to be at scale, or how it's going to appease all of these customers, but then you have to recognize that it is a long hallway to get there. You've got to start somewhere, and you've got to start somewhere that's easy, and that's going to captivate an audience before you actually get to that platform play, if you will. That's really the role of product here, because we have so many design thinkers, we have business folks, we have people that are like, "Oh, well can't we just do this?" This is great. We pitched three concepts last week, and after all three were over, there was a couple people in the room that were like, "Let's just combine those. That's perfect. That product would be amazing."

We're like, "Yeah, that product would be amazing if you want it in ten years. You don't understand what you just asked for, and it just proves that you're not understanding what the customer's pain point it. We need to figure out what that actually pain point is, and try to solve it, because if we can solve that really well, well then we can add these other pieces as features." I think that having that clarity as a PM is really important. You do have to remind yourself of that, because you can get hung up. I've done it. I did it on my own startup. I spent way too long trying to get all of the features in, without recognizing how complex it was getting before we had really gotten good feedback from a user. Live and learn, I guess.

interesting. You'll see some things in there, and a lot of it's geared towards how to develop products when people are irrational. You might think, "There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this. There's no way they would choose this." Then, sure enough, "Boom." Everybody chooses it.

Suzanne: You mean as customers, or even internally?

Tyler: Both. Yeah, it kind of has both perspectives throughout the book, but it's great. You should definitely read it.

Suzanne: The danger, too, is always ... We know so much about all of these different disciplines that we cook up all of these assumptions all the time about how other people outside of the world of product think about user experience, think about design, think about features. It's funny, the number one problem is jumping to the solution, because that's the fun stuff, when you say it.

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: How do you insert into your memory muscle, "Don't leap from an unexamined assumption to build. Remember to go through those boring steps that you probably all do here in innovation." How do you insert it so that you don't forget to make the same mistakes that you're trying to teach your clients not to make?

Tyler: It's a hard one. It is a hard one, because you have a grand vision of what something's going to look like, or how you want it to be at scale, or how it's going to appease all of these customers, but then you have to recognize that it is a long hallway to get there. You've got to start somewhere, and you've got to start somewhere that's easy, and that's going to captivate an audience before you actually get to that platform play, if you will. That's really the role of product here, because we have so many design thinkers, we have business folks, we have people that are like, "Oh, well can't we just do this?" This is great. We pitched three concepts last week, and after all three were over, there was a couple people in the room that were like, "Let's just combine those. That's perfect. That product would be amazing."

We're like, "Yeah, that product would be amazing if you want it in ten years. You don't understand what you just asked for, and it just proves that you're not understanding what the customer's pain point it. We need to figure out what that actually pain point is, and try to solve it, because if we can solve that really well, well then we can add these other pieces as features." I think that having that clarity as a PM is really important. You do have to remind yourself of that, because you can get hung up. I've done it. I did it on my own startup. I spent way too long trying to get all of the features in, without recognizing how complex it was getting before we had really gotten good feedback from a user. Live and learn, I guess.

Suzanne: Right. Have you hung up your entrepreneurial badge, or do you think there might be one more garage business in your future?

Tyler: There's probably 30 garage businesses in my future. I was on The Amazing Race, and so-

Suzanne: Do you just win at things? This is the advice, "If you take up the "Get shit done" mantra, it will equal to "Win startup weekend. Be in The Amazing Race."

Tyler: Yeah.

Suzanne: We need another episode just for your accolades.

Tyler: No. I'm obsessed with traveling, and I've been working on something on the side recently that's in the travel space, that I'm excited about. I'll sleep when I'm dead. Ever since then it's just been like, "I've got to do something with travel," and I feel like there's a big opportunity in travel right now, but I'm in the same position that I'm in when we work with our clients. It's like, "Okay, I know what the vision is for this thing. I know what it looks like at scale." MVP is very hard to start, and be able to get people's attention that would eventually allow you to get there. It's taking those steps backwards, and really being smart about where you begin that enables you to be successful. Really refining that first iteration of it is where I'm at right now, but it's super fun.

Suzanne: This is my last question for today. Do you have advice for the people listening in, people who are just dipping toe into this world of entrepreneurship and product? Something from your long travels through this space?

Tyler: Yeah, only work on it if you love it. I think that if you're working on it because you want to make a lot of money, or if you're working on it because somebody else did it, and you thought it looked kind of cool, you're going to fail. You have to absolutely love it, and absolutely believe in it, because if you don't, you're going to wake up one day, and you're going to ask yourself what you're doing, and you're going to lose all of the momentum you had. I think any entrepreneur that's worked on a number of projects has had that happen at least once, so you start to realize that. Just really make sure that you love it, because if you love it, you're going to be successful in some degree. It might not be the next billion dollar idea, but there's going to be a level of success that comes out of it. If you're just doing it for the wrong reasons, it's wasting your time.

Suzanne: Beautiful. Thank you so much for your time, Tyler. I really appreciate it.

Tyler: Yeah. Thanks.

In this episode:

- Where do startups go wrong with implementing OKRs

- Can OKRs really scale for enterprise?

- What are pipelines and how do they change the way we think about product roadmaps?

In this episode:

- From retail to product management

- Why relationship building is the number one required skill a product manager could have

- The value of having confidence with humility

In this episode:

- Establishing a clear vision of your career path

- Using metrics to answer burning product questions

- What product managers can learn from biology